A more plant-centered diet helps to boost immunity and control inflammatory responses that raise the risk of chronic disease. By Teri Mosey, PhD

Many of the foods we eat—especially vegetables—can help us deal with the double-edged sword of inflammation.

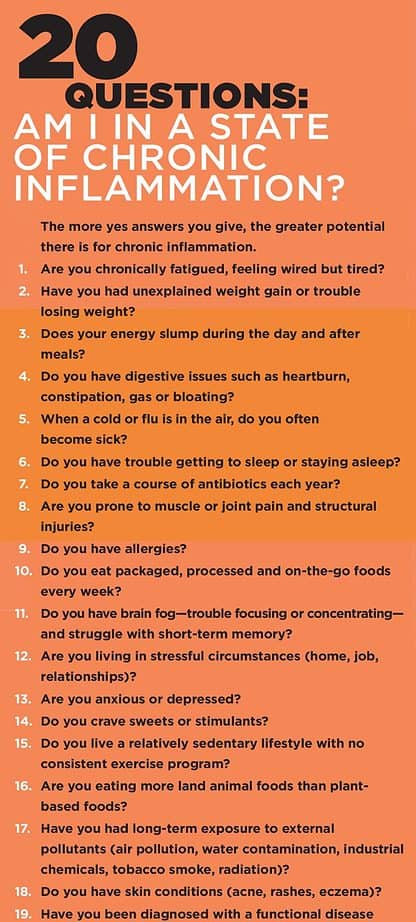

Acute inflammation is the good edge of the blade. It’s painful but essential because, by telling the body that injured tissues require immediate attention, it triggers immune reactions that help us heal. Chronic inflammation, however, is the bad edge. It plays a central role in heart disease, cancer, neurological disorders, autoimmune diseases, pulmonary conditions, anxiety, and depression. It’s also implicated in Parkinson’s disease, type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, osteoporosis, asthma, and weight struggles (Barnes & Celli 2009; Beal 2003; Dowlatshahi et al. 2013; Esser et al. 2014; Tilg et al. 2008; Yudkin et al. 2000).

Ideally, inflammation is part of an alarm system. Think about when you slice your finger with a knife, sprain your ankle on a hike, or endure a 24-hour stomach virus. Inflammation begins a sequence of immune responses that support your recovery. A scab forms on your finger, ankle swelling goes down, and the digestive system rebalances. Then the immune system shuts off the inflammation alarm and resumes working behind the scenes to keep you in a harmonious, healthy state.

Troubles begin when the inflammation alarm doesn’t shut off entirely and keeps sending a low-grade immune response. You can stay in an inflammatory yet somewhat functional state for months, years, or decades before symptoms become disruptive enough to notice. Eventually, low-grade inflammation produces problems like high blood pressure, sugar imbalances, and asthma. Staying even longer in this state raises the risk of heart attacks, diabetes, and pulmonary disease.

Inflammation will always be essential to our immune defense. Coping with the double-edged sword is not about silencing inflammation—it’s about controlling it. Diet can help us do that.

We can study single nutrients to see how they influence physiological mechanisms like inflammation and immunity. However, a nutrient’s impact happens only in the context of every other nutrient, chemical substance, and hormone released in the body. Thus, no nutrient alone will fight chronic inflammation and keep you disease-free.

Everything in the body is interconnected—it’s a holistic network with no isolated heroes (see “Diet, Inflammation and the Body’s Holistic System,” below). We have to see the roles of individual nutrients in the context of foods, meals, diets, and most importantly, the person doing the eating.

Indeed, the individual is the most critical variable. We all digest food differently based on variables such as how well we chew our food, stomach acidity, digestive enzyme release, gut bacteria health, state of mind, stress levels, and immune status. The foods we eat over and over, every day, across extended periods have the most impact on our body’s functioning.

Two key actions can help you and your clients use food to manage inflammation and strengthen immunities: eating more vegetables and protecting your gut microbiome. Let’s dive into these.

Plant-Based Diets and Inflammation

Research recommends eating more plants for their anti-inflammatory qualities and antioxidant cellular-regeneration properties (Kahleova et al. 2011; Liu 2013; Tuso et al. 2013; Tuso, Stoll & Li 2015). Our world exposes us to disruptive pollutants and toxins via the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the foods we eat. All these threats require our bodies to adapt.

Choosing a primarily plant-based diet limits inflammation and supports the immune system, encouraging the body’s natural healing and cellular renewal. Plant-based foods are fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, beans, nuts, and seeds. Note the modifier primarily. Not everyone should adopt a vegetarian or vegan eating philosophy. It’s just that a more plant-focused diet supports the immune system with an abundance of nutrients that you can’t get from animal sources.

Moreover, a food’s packaging, nutrient composition, and chemical makeup play important roles in the biochemical pathways activated after digestion—either supporting immunity or exacerbating inflammation. All these factors weigh in the favor of plant-based foods (Eichelmann et al. 2016; Watzl 2008; Zinocker & Lindseth 2018).

Phytonutrients and Fiber

Two primary plant-based supporters of the immune system are phytonutrients and fiber. Phytonutrients are bioactive plant compounds that enhance immunity, repair tissues and DNA damage from toxin exposure, support the body’s detoxification processes, and promote positive gene expressions toward health. Among the thousands of phytonutrients, scientists have identified three categories that pack a powerful protective punch: glucosinolates, flavonoids, and carotenoids.

- Glucosinolates have been found to fight inflammation, support detoxification pathways, and possibly protect against cancers. They’re found predominantly in cruciferous vegetables—arugula, broccoli, bok choy, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, mustard greens, and kale (Bosetti et al. 2012; Jiang et al. 2014; Tilg 2015; Lam et al. 2009).

- Flavonoids help regulate gene expression to prevent chronic ailments such as heart disease, cancer, neurological disorders, and digestive illnesses. Flavonoids are found in berries, red grapes, citrus, and green tea (Gonzalez-Gallego et al. 2010; Kumar & Pandey 2013; Serafini, Peluso & Raguzzini 2010).

- Carotenoids are known for their antioxidant properties, particularly against heart disease and cancers. They’re found in sweet potatoes, carrots, squash, and tomatoes (Agarwal & Rao 2000; Rao & Rao 2007).

From this small sample, you may notice that selecting these foods would make your meals quite colorful. That’s because many phytonutrients dwell in the pigments of plants—the scientific rationale for “eating a rainbow diet.”

Fiber is another crucial plant-based supporter of the immune system, giving a significant boost to the population of friendly gut bacteria and bolstering the case for a plant-based diet (Menni et al. 2017; Singh et al. 2017). Consuming fiber through foods such as lentils, apples, berries, avocado, quinoa, almonds, and oats help regulate blood sugar levels and maintain healthy colon function. Fiber also influences inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6. Soluble and insoluble fibers both play a role in health. Research is demonstrating a link between total fiber consumption and a significant risk reduction for heart disease, diabetes, and systemic inflammation (King 2005; Krishnamurthy et al. 2012; Ma et al. 2008; Qi et al. 2006).

Adults are urged to consume about 25–30 grams of fiber daily to enjoy these benefits. Shifting to a primarily plant-based diet will help you meet these fiber standards with little extra effort.

Diet, Inflammation, and the Body’s Holistic System

The human body is a perfect example of holistic design—everything about it is interconnected (Lipton 2015; Pert 1999; Sternberg 2001). All of our organs, tissues, thoughts, and emotions operate in a cohesive network. If we wish to restore health in our clients, manage the inflammation alarm, and age gracefully without chronic disease, we have to stop seeing the body as machine-like and start to see it as a holistic network being.

Diet is a big deal because the gut has a brain. The enteric nervous system in the lining of the esophagus, stomach, small intestines, and colon contains 100 million neurons—more than the number running up and down the spine. Your gut-brain does more than digest foods. It helps with regulating immunity and coordinating neurotransmitter and hormone secretions while influencing cognitive function. The gut-brain affects your emotions, sensitivity to pain, sleep patterns, and even how you socialize and make decisions (Liu & Zhu 2018; Rosselot, Hong & Moore 2016; Wu & Wu 2012). All this happens independently of the brain in your head.

Your immune system adds another level of complexity. Billions of cells on the skin, in the lining of the lungs, and flowing through the bloodstream throughout the digestive tract protect you from external and internal pollutants. The external ones include pesticide residues, chemicals in food, and an assortment of toxins, pathogens, and particulates in the air and water. The biggest internal pollutant is stress, which has a direct link to inflammation and chronic illness (Cohen 2012; Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser 2005; Innala et al. 2016; Miller, Cohen & Ritchey 2002; Segerstrom & Miller 2004; Slavich & Irwin 2014).

The immune system monitors the body on a cellular and molecular level to maintain a harmonious, healthy inner state called homeostasis. The immune system is such an active communicator that immune cells contain every type of brain receptor, making this system a regulator of emotions. Do you see the complexity? Your brain is enmeshed in your immune system, which is trapped in your gut. They cannot be separated.

Thus, managing chronic inflammation means enhancing the body’s ability to heal itself. Fortunately, research is continually revealing more secrets about the mechanisms of immunity. One finding is that our food choices are primary influencers in the immune system. Everything about our diet plays a role in supporting or breaking down the body’s anti-inflammatory defense.

Feed Your Microbiome

We used to associate bacteria with illness and uncleanliness. Now, we understand that bacteria play a crucial role in our immunity and well-being. Through the Human Microbiome Project, researchers are learning about a hundred trillion microbes all over the body—on the skin, in the nose and mouth, and in the gut (where they collectively weigh about 3–4 pounds) (NIH 2012). All these variables mean your body is an ecosystem unique to you.

Current research estimates that 70% of our immune cells reside in the gut. The lining of the intestinal wall is the interface between you and the outside world, with more immune cells here than are circulating throughout the body. This intestinal lining is essential in determining what the body absorbs. The microbiome also teaches the immune system to recognize something foreign or harmful without attacking itself, which happens with autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, Crohn’s disease, and lupus.

The gut microbiome influences all aspects of human function: immune responses, detoxification processes, neurotransmitter and hormone production, nutrient absorption, libido, mood, memory, and even the clarity of our thoughts. The microbiome has a direct impact on metabolism because it affects how the liver and muscles store and use energy. It also influences the insulin sensitivity of cells to regulate blood sugar levels, appetite, and weight gain.

Additionally, a diversified microbiome of friendly bacteria keeps stress responses in check by triggering the gut-brain to release neurotransmitters such as GABA, serotonin, and dopamine to ward off anxiety and depression. Researchers are finding that the more we care for our microbiome—where the strains and diversity of bacteria can shift in only a few days—the better we do at supporting long-term immunity and decreasing chronic disease (Belkaid & Harrison 2017; Belkaid & Hand 2014; Clemente, Manasson & Scher 2018; Gonzalez et al. 2011; Paun, Yau & Danska 2017; Slingerland et al. 2017; van de Meulen et al. 2016).

Diet can improve the well-being of the microbiome. You can eat prebiotics, which feeds the present gut bacteria, and probiotics, which contain live microbes. Choosing both options can keep your microbiome diverse and well-fed.

- Prebiotics include raw garlic, raw red onion, leeks, bananas, peas, and dandelion greens.

- Probiotics include naturally fermented cabbage, kimchi, tempeh, miso, and apple cider vinegar. They add diversity because each strain of bacteria has different metabolic and immunological functions.

While plant-based foods help the microbiome, research is finding that animal-based foods can be troublesome. The research is in its infancy, but some studies suggest that saturated fats, high-fat foods from land animals, and high-protein diets damage the composition of gut bacteria. Meanwhile, unsaturated and polyunsaturated fats from nuts, seeds, and fatty fishes, such as salmon and halibut, can help with microbiome health and anti-inflammatory processes when part of a primarily plant-based diet (Candido et al. 2018; Zhang & Yang 2016).

Choosing a primarily plant-based diet with a conscious effort to feed your microbiome is the most effective way to strengthen your body’s anti-inflammatory defense. Understand that everything about you is in constant flux. Your immune responses, regeneration process, microbiome health, and genetic expression change constantly, depending on your everyday dietary choices. While these practical strategies provide a great place to start, it’s not that simple. There’s another level to the food–inflammation connection.

It’s Never Just About Food

Our relationship with food goes beyond calories and physical nutrients. Where the food came from, meal preparation techniques, eating environment, and our state of mind influence the experience.

Our state of mind has a major impact on healthy digestion and the body’s inflammation alarm system. Research into psychoneuroimmunology is identifying the biochemical link between body and mind. Studies suggest that every thought causes the brain to release biochemicals called neuropeptides in the body so you can feel what you are thinking. And most of your daily thoughts are the same as they were yesterday, creating a specific biochemistry we call your state of being.

Thus, thought patterns affect your physical health. Love, playfulness, worry, and fear release specific neuropeptides, generating a corresponding chemistry. Research is now mapping the physiological differences these emotions cause.

One major breakthrough is the impact of stress. Stressful emotions—including grief, shame, frustration, anger, or fear—activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) stress response axis, releasing pro-inflammatory proteins called cytokines to set off the inflammation alarm. This network response happens because many nerve pathways and molecules underlying both psychological responses and inflammatory diseases are the same (Cohen & Herbert 1996; Dinan & Cryan 2017; Haroon, Raison & Miller 2012; Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 2002; Sternberg 2001; Straub & Cutolo 2018). This means your thoughts can create inflammation even without other causes.

Think about how this affects our relationship with food and its contribution to the body’s anti-inflammatory defense. Stress activates inflammatory pathways when guilt or shame triggers an urge to eat, binging and deprivation lock us in an unhealthy cycle, and rigid food rules limit our dietary diversity. These forces decrease the absorption and utilization of nutrients, initiating the onset of diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, obesity, arthritis, and depression (Cohen et al. 2012; Kiecolt-Glaser 2010; Rosenberg et al. 2013; Steptoe & Kivimaki 2012).

Getting Your Mind Right

How do you limit the stress-inflammation response? Begin by practicing mindfulness meditation techniques. Research shows the power of mindfulness, including mindful eating, in lowering stress responses, managing inflammation, and helping us shift to more health-supportive eating behaviors (Fountain-Zaragoza & Prakash 2017; Jordan et al. 2014; Pintado-Cucarella & Rodriguez-Salgado 2016). The more mindfully you eat, the healthier you will be.

15 Diet Habits That Support Immunity

- Eat a whole-food, primarily plant-based diet.

- Consume 25–30 grams of fiber daily.

- Eat a majority of meals cooked – 90% cooked and 10% raw.

- Eat organic whenever possible.

- Choose mostly unsaturated fat sources (nuts, seeds, avocado, salmon, and halibut) and limit saturated-fat consumption (land animals, dairy, fried foods, and bakery goods).

- Feed your microbiome with prebiotics, leeks and bananas, and fermented foods, such as sauerkraut and tempeh.

- Remove processed and packaged foods from your everyday diet.

- Limit stimulants such as coffee to occasional use; they shouldn’t be required for daily functioning.

- Slow down and chew food thoroughly.

- Limit eating amid stressful emotions like worry, grief, shame, frustration, or anger.

- Avoid processed sugars and artificial sweeteners.

- Cook with healing spices and herbs, including turmeric, cumin, cinnamon, ginger, basil, fennel, cayenne, cloves, and black pepper.

- Diversify your diet by eating on at least a 4-day rotation, with a new food incorporated weekly.

- Be fully present for the dining experience. Eat mindfully.

- Get in the kitchen and play a proactive role in your health. Know exactly what’s in your meals.

What’s the Take-Home Message?

Food is a strong initiator of healing, contributing to long-term health. But it does not act alone. Everything about you is part of a cohesive network where your physical, mental, and emotional states influence the inflammation-immune defense.

Think about combining a whole-food, primarily plant-based diet with mindfulness exercises. Then you can begin to use your relationship with food as medicine—keeping inflammation at bay and preventing the onset of chronic disease.

References

Agarwal, S., & Rao, A.V. 2000. Tomato lycopene and its role in human health and chronic diseases. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 163 (6), 739–44.

Barnes, P.J., & Celli, B.R. 2009. Systemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPD. European Respiratory Journal, 33 (5), 1165–85.

Beal, M.F. 2003. Mitochondria, oxidative damage, and inflammation in ParkinsonÔÇÖs disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 991, 120–31.

Belkaid, Y., & Hand, T.W. 2014. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell, 157 (1), 121–41.

Belkaid, Y., & Harrison, O.J. 2017. Homeostatic immunity and the microbiota. Immunity, 46 (4), 562–76.

Bosetti, C., et al. 2012. Cruciferous vegetables and cancer risk in a network of case-control studies. Annals of Oncology, 23 (8), 2198–203.

Candido, F.G., et al. 2018. Impact of dietary fat on gut microbiota and low-grade systemic inflammation: mechanisms and clinical implications on obesity. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 69 (2), 125–43.

Clemente, J.C., Manasson, J., & Scher, J.U. 2018. The role of the gut microbiome in systemic inflammatory disease. BMJ, 360, j5145.

Cohen, S., & Herbert, T.B. 1996. Health psychology: Psychological factors and physical disease from the perspective of human psychoneuroimmunology. Annual Review of Psychology, 47, 113–42.

Cohen, S., et al. 2012. Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109 (16), 5995–99.

Dinan, T.G., & Cryan, J.F. 2017. Microbes, immunity, and behavior: Psychoneuroimmunology meets the microbiome, Neuropsychopharmacology, 42 (1), 178–92.

Dowlatshahi, E.A., et al. 2013. Markers of systemic inflammation in psoriasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Dermatology, 169 (2), 266–82.

Eichelmann, F., et al. 2016. Effect of plantÔÇÉbased diets on obesityÔÇÉrelated inflammatory profiles: A systematic review and metaÔÇÉanalysis of intervention trials. Obesity Reviews, 17 (11), 1067–79.

Esser, N., et al. 2014. Inflammation as a link between obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 105 (2), 141–50.

Fountain-Zaragoza, S., & Prakash, R.S. 2017. Mindfulness training for healthy aging: Impact on attention, well-being, and inflammation. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 9 (11).

Glaser, R., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. 2005. How stress damages the immune system and health. Discovery Medicine, 5 (26), 165–69.

Gonzalez, A., et al. 2011. The mind-body-microbial continuum. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13 (1), 55–62.

Gonzalez-Gallego, J., et al. 2010. Fruit polyphenols, immunity and inflammation. British Journal of Nutrition, 104 (3 Suppl.), S15–27.

Haroon, E., Raison, C.L., & Miller, A.H. 2012. Psychoneuroimmunology meets neuropsychopharmacology: Translational implications of the impact of inflammation on behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology, 37 (1), 137–62.

Innala, L., et al. 2016. Co-morbidity in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis—inflammation matters. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 18 (33).

Jiang, Y., et al. 2014. Cruciferous vegetable intake is inversely correlated with circulating levels of proinflammatory markers in women. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 114 (5), 700–8.

Jordan. C.H., et al. 2014. Mindful eating: Trait and state mindfulness predict healthier eating behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 107–11.

Kahleova, H., et al. 2011. A vegetarian diet improves insulin resistance and oxidative stress markers more than a conventional diet in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine, 28 (5), 549–59.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. 2010. Stress, food, and inflammation: Psychoneuroimmunology and nutrition at the cutting edge. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72 (4), 365–69.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K., et al. 2002. Emotions, morbidity, and mortality: New perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 83–107.

King, D.E. 2005. Dietary fiber, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research, 49 (6), 594–600.

Krishnamurthy, V.M., et al. 2012. High dietary fiber intake is associated with decreased inflammation and all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney International, 81 (3), 300–6.

Kumar, S., & Pandey, A.K. 2013. Chemistry and biological activities of flavonoids: An overview. Scientific World Journal, doi:10.1155/2013/162750.

Lam, T.K., et al. 2009. Cruciferous vegetable consumption and lung cancer risk: A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, and Prevention, 18 (1) 184–95.

Liisberg, U., et al. 2016. The protein source determines the potential of high-protein diets to attenuate obesity development in C57BL/6J mice. Adipocyte, 5 (2), 196–211.

Lipton, B.H. 2015. The Biology of Belief. Carlsbad, California: Hay House.

Liu, R.H. 2013. Health-promoting components of fruits and vegetables in the diet. Advances in Nutrition, 4 (3), 384S–92S.

Liu, L., & Zhu, G. 2018. Gut-brain axis and mood disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9 (223).

Ma, Y., et al. 2008. Association between dietary fiber and markers of systemic inflammation in the WomenÔÇÖs Health Initiative Observational Study. Nutrition, 24 (10), 941–49.

Menni, C., et al. 2017. Gut microbiome diversity and high-fiber intake are related to lower long-term weight gain. International Journal of Obesity, 41 (7), 1099–105.

Miller, G.E., Cohen, S., & Ritchey, A.K. 2002. Chronic psychological stress and the regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines: A glucocorticoid-resistance model. Health Psychology, 21 (6), 531–41.

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2012. NIH Human Microbiome Project defines the normal bacterial makeup of the body. Accessed Apr. 24, 2019: https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-human-microbiome-project-defines-normal-bacterial-makeup-body.

Paun, A., Yau, C., & Danska, J.S. 2017. The influence of the microbiome on type 1 diabetes. Journal of Immunology, 198 (2), 590–95.

Pert, C.B. 1999. Molecules of Emotion. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Pintado-Cucarella, S., & Rodriguez-Salgado, P. 2016. Mindful eating and its relationship with body mass index, binge eating, anxiety, and negative affect. Journal of Behavior, Health & Social Issues, 8 (2), 19–24.

Qi, L., et al. 2006. Whole-grain, bran, and cereal fiber intakes and markers of systemic inflammation in diabetic women. Diabetes Care, 29 (2), 207–11.

Rao, A.V., & Rao, L.G. 2007. Carotenoids and human health. Pharmacological Research, 55 (3), 207–16.

Rosenberg, N., et al. 2013. Cortisol response and desire to binge following psychological stress: Comparison between obese subjects with and without binge eating disorder. Psychiatry Research, 208 (2), 156–61.

Rosselot, A.E., Hong, C.I., & Moore, S.R. 2016. Rhythm and bugs: Circadian clock, gut microbiota, and enteric infections. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology, 32 (1), 7–11.

Segerstrom, S.C., & Miller, G.E. 2004. Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychological Bulletin, 130 (4), 601–30.

Serafini, M., Peluso, I., & Raguzzini, A. 2010. Flavonoids as anti-inflammatory agents. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 69 (3), 273–78.

Singh, R.K., et al. 2017. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. Journal of Translational Medicine, 15 (1), 73.

Slavich, G.M., & Irwin, M.R. 2014. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: A social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychological Bulletin, 140 (3), 774–815.

Slingerland, A.E., et al. 2017. Clinical evidence for the microbiome in inflammatory diseases. Frontiers in Immunology, 8 (400).

Steptoe, A., & Kivimaki, M. 2012. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 9 (6), 360–70.

Sternberg, E.M. 2001. The Balance Within. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Straub, R.H., & Cutolo, M. 2018. Psychoneuroimmunology—developments in stress research. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift, 168 (3–4), 76–84.

Tilg, H. 2015. Cruciferous vegetables: Prototypic anti-inflammatory food components. Clinical Phytoscience, 1 (10), 1–6.

Tilg, H., et al. 2008. Gut, inflammation, and osteoporosis: Basic and clinical concepts. Gut, 57 (5), 684–94.

Tuso, P.J., et al. 2013. Nutritional update for physicians: Plant-based diets. Permanente Journal, 17 (2), 61–66.

Tuso, P.J., Stoll, S.R., & Li, W.W. 2015. A plant-based diet, atherogenesis, and coronary artery disease prevention. The Permanente Journal, 19 (1), 62–67.

van de Meulen, T.A, et al. 2016. The microbiome-systemic diseases connection. Oral Diseases, 22 (8), 719–34.

Watzl, B. 2008. Anti-inflammatory effects of plant-based foods and of their constituents. International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research, 78 (6), 293–98.

Wu, H.J., & Wu, E. 2012. The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut Microbes, 3 (1), 4–14.

Yudkin, J.S., et al. 2000. Inflammation, obesity, stress, and coronary heart disease: Is interleukin-6 the link? Atherosclerosis, 148 (2), 209–14.

Zhang, M., & Yang, X-J. 2016. Effects of a high-fat diet on intestinal microbiota and gastrointestinal diseases. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 22 (40), 8905–9.

Zinocker, M.K., & Lindseth, I.A. 2018. The western diet-microbiome-host interaction and its role in metabolic disease. Nutrients, 10 (3), 365.

Teri Mosey, PhD

Teri Mosey is the founder of Holistic Pathways and has been working in various areas of the health and fitness industry since 1996. Her knowledge and experience have developed over the years to include studies of Eastern and Western philosophies, yogic perspectives, energy medicine, meditative practices, and culinary exploration. Through personal and group dynamics, Teri provides supportive and resourceful environments to assist others in discovering their personal path to wellness. She presents alternative perspectives of biochemistry, human physiology, and nutrition by incorporating the principles of holistic living into her work. Teri believes with a dynamic foundation of knowledge combined with personal responsibility and freedom of choice, we can all recognize the power within us to co-create our health and ultimately our lives.

Please review our business at: Google Yelp Facebook

If you’d like to learn more, please visit our Member’s Area to access our subscribed content.

Did you know you can work out and exercise with a trainer at your home, office, hotel room, or anywhere in the world with online personal training?

Like us on Facebook/Connect with us on LinkedIn/Follow us on Twitter

Make sure to forward this to friends and followers!